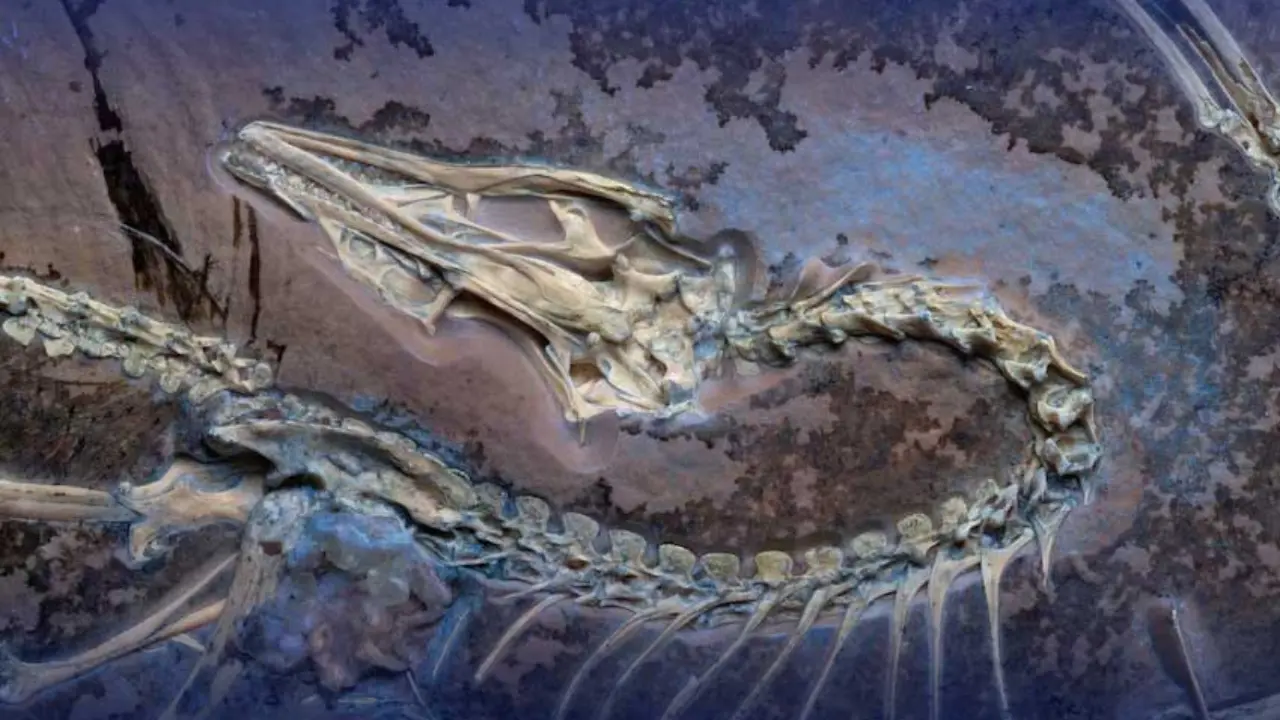

Chicago — A 150-million-year-old fossil is lighting up evolutionary science—literally. Using ultraviolet light and CT scans, scientists have uncovered astonishing new details about Archaeopteryx, the iconic “dino-bird” that once bridged the prehistoric gap between reptiles and modern birds.

The fossil, housed at the Field Museum in Chicago and hailed as possibly the best-preserved specimen of its kind, is unlocking mysteries that have eluded scientists for over 160 years. Discovered in southern Germany and hidden in private collections for decades, the fossil is now at the center of a groundbreaking new study published in Nature.

“It’s arguably the most important fossil ever discovered,” said paleontologist Jingmai O’Connor, the study’s lead author. “It’s the icon of evolution—proof that birds are living dinosaurs.”

Unlike previous flattened fossils, this three-dimensional marvel reveals never-before-seen soft tissue and skeletal features under UV light. Among the surprises: Archaeopteryx had tertial feathers—specialized flight feathers found in modern birds. These feathers, previously unknown in feathered dinosaurs, hint that true powered flight was already taking shape.

“To fly, birds needed a seamless aerodynamic surface connected to the body,” explained O’Connor. “These tertials helped close that gap, pushing the evolution of flight forward.”

But this ancient flyer wasn’t a full-time sky dweller. The structure of its toe pads and hands suggests Archaeopteryx spent much of its time grounded, capable of climbing trees but probably not soaring high like modern birds. Its claws, stiff tail, and fixed skull showed a strange mix of traits—half bird, half dinosaur.

Even its mouth holds clues. The palate structure hints at an early version of cranial kinesis, the jaw mobility seen in birds today. Meanwhile, the fossil includes the only complete vertebral column ever found in Archaeopteryx, adding an extra vertebra to its known anatomy—24 in total.

“This fossil is rewriting what we thought we knew about how flight evolved,” said Alex Clark, a University of Chicago PhD student and co-author. “It’s a time capsule from the dawn of birds.”

Unearthed before 1990 and finally acquired by the museum last year, the fossil is now propelling a new era of discovery. For scientists and dinosaur fans alike, this dino-bird still has plenty of flight left in it.

From teeth to feathers, claws to wings—Archaeopteryx is soaring back into the spotlight as evolution’s greatest missing link.